Over the last few years, “nervous system” has become a mainstream phrase.

We talk about regulation, dysregulation, vagus nerve hacks, trauma, and safety cues.

Much of that is helpful. But there’s a part of the story that’s often missing:

What is actually fuelling the system we’re trying to regulate?

We can’t keep talking about nervous systems in isolation from mitochondria, metabolism and energy. If we want a nervous system that can adapt, recover, and stay flexible, we have to talk about how well it’s powered.

Linking Metabolism and the Nervous System

Every thought, emotion, movement and stress response in your body runs on energy.

That energy is produced, moment by moment, inside your cells by tiny organelles called mitochondria. They take the food you eat and the oxygen you breathe and convert them into ATP, the chemical energy your cells use to do their work.

Your brain is particularly demanding. It represents roughly 2% of your body weight, yet uses about 20% of your resting energy. If mitochondrial function is compromised, through stress, inflammation, poor sleep, illness, metabolic issues or simply accumulated wear and tear, your brain and nervous system are impacted.

This is where we start to see problems like:

- Brain fog and slowed thinking

- Anxiety & depression

- Inability to switch off

- Emotions that are out of balance

- Poor stress tolerance and recovery

We often describe these as purely “mental health” or emotional issues, but underneath, there may be a very physical problem:

The nervous system is trying to do complex work on a low or unstable energy supply.

Metabolic flexibility: why fuel switching matters for stress adaptation

It isn’t just about how much energy you can produce, but how flexibly you can produce it.

Metabolic flexibility is your body’s ability to switch between fuel sources (mainly fats and carbohydrates) depending on what is being asked of you:

- Sitting at your desk vs walking to a meeting

- Sleeping vs giving a presentation

- A calm day vs a stressful deadline

A flexible metabolism is like a hybrid car that can move smoothly between petrol and electric. Your system chooses the most efficient, appropriate fuel for the situation.

When metabolic flexibility is reduced, people often describe:

- Sudden crashes in energy or mood

- Needing caffeine or sugar to function

- Feeling hyperaroused or hypoaroused

- Irritability or anxiety that feels out of proportion to what’s actually happening

From the outside, we call this stress, burnout or emotional dysregulation.

Internally, it’s often a fuel selection problem as much as a psychological one. Your cells can’t transition smoothly between different levels of demand.

If adaptation is the nervous system’s job, then metabolic flexibility is one of its key tools.

The growing evidence: mitochondria, metabolism and mental health

For decades, research has been quietly linking mitochondrial dysfunction to a wide range of psychiatric conditions: depression, anxiety, mood disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders, among others.

Findings have included:

- Changes in mitochondrial structure and function in the brains of people with mood and psychotic disorders

- Impaired oxidative phosphorylation, the process mitochondria use to make ATP, in depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia

- High rates of significant mental health symptoms in people with primary mitochondrial diseases

In other words, energy problems in brain cells show up as mental health problems in real life.

Psychiatrist Dr Chris Palmer has pulled many of these strands together in his book Brain Energy, arguing that mental disorders are, at their core, metabolic disorders of the brain. His “Brain Energy” model doesn’t deny psychological or social factors. Instead, it suggests that:

- Stress, trauma, genetics, lifestyle and environment all impact cellular metabolism

- When mitochondrial function is impaired, brain circuits struggle to fire and adapt normally

- This can help explain why mental illness so often overlaps with metabolic conditions like obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease The Broken Science Initiative

You don’t have to fully endorse any single theory to see the direction of travel:

energy metabolism is no longer a side note in mental health. It’s central.

Stress recovery as an energy problem, not just a mindset problem

If we bring this back to everyday stress recovery, a pattern emerges.

Most high-functioning adults I work with are not in crisis. They’re often:

- Responsible, reflective, and engaged in meaningful but demanding work

- Have experienced past adversity and have moved beyond

- But noticing that their energy, resilience and flexibility have quietly eroded

They might say things like:

- “ I don’t bounce back the way I used to.”

- “My sleep is okay on paper, but I still feel unrefreshed.”

- “Small stresses feel bigger than they should.”

- “I feel like my nervous system is out.”

If we only treat this as a psychological or emotional issue, adjust thoughts, practise coping strategies, add a few nervous system “tools” , we can easily miss the underlying constraint:

Their energy production and fuel flexibility are not keeping up with the demands of their life.

From a physiological perspective, effective stress recovery requires that you can:

- Mount a response: mobilise resources when something challenging happens

- Complete the response: process, act, decide, respond

- Return to baseline: shift back into a state where repair, digestion and long-term health processes can take place

Mitochondria and metabolism sit inside each phase:

- Can you produce enough energy quickly when needed?

- Can you maintain that output without burning out?

- Can you efficiently downshift and redirect energy into recovery and repair?

If the answer is “not really” at any point, your nervous system feels it, no matter how many calming techniques you know.

What this means in practice

For me, this is why conversations about the nervous system need to widen to include mitochondria, metabolism and energy.

It doesn’t mean everyone needs to become a biohacker, or that psychological work no longer matters. It means that:

- We stop pretending we can “regulate” a system that is chronically under-fuelled

- We ask questions about energy stability, not just mood

- We pay attention to metabolic flexibility as a marker of resilience:

- How do you cope with gaps between meals?

- How does your body respond to stress in the moment and after the event?

- Does stress drive you towards higher-calorie foods?

- Can you sustain energy and concentration across the day?

And in terms of interventions, it suggests layers, not quick fixes:

- Foundations like sleep, blood sugar balance, movement and breathing are still essential because they all influence mitochondrial function and metabolic health.

- More targeted approaches (from specific nutrition strategies through to technologies like neurofeedback or oxygen-based interventions) may help train the system to adapt more efficiently to stress and recovery demands over time.

For people who have already done the psychological work and found it only got them so far, this is often the missing piece:

Moving from “I understand why I feel this way” to “my body and brain actually have the capacity to feel and function differently.”

Bringing energy into the nervous system space

Nervous system language has helped many people make sense of their experience. But if we stop at “dysregulated nervous system”, we risk giving a name to the problem without addressing what’s fuelling it.

Mitochondria, metabolism and energy production are not niche interests. They’re part of the infrastructure that allows your nervous system to do its job:

to sense, respond, adapt and recover in a world that isn’t going to stop being demanding.

If we want more robust, long-term outcomes in stress recovery and mental health, it’s time to give energy a proper place in the conversation.

If you recognise yourself in this, functioning on the outside, but feeling your energy and resilience have quietly eroded, the next step is to look at how we can support both your nervous system and your energy systems in practice.

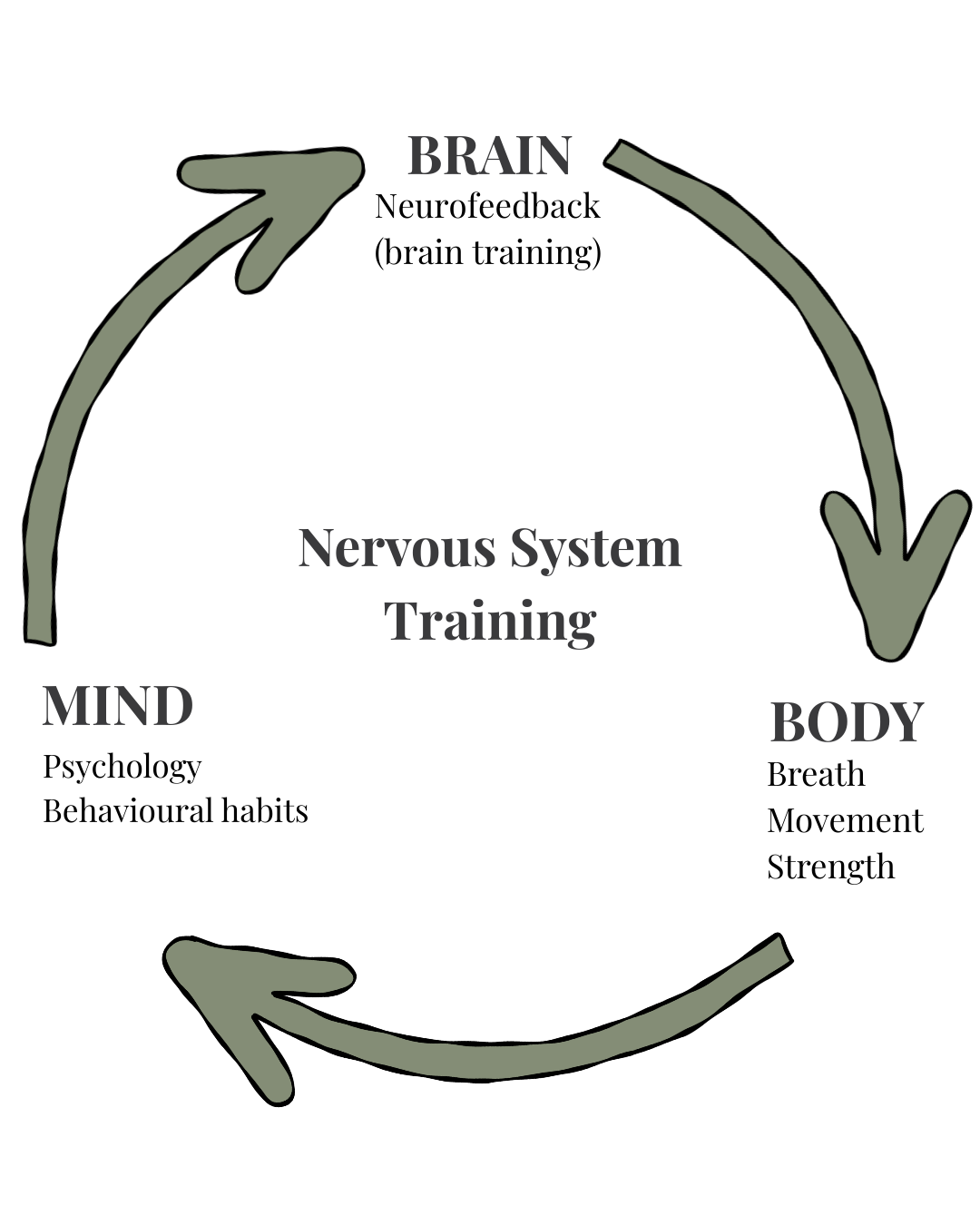

About BodyMindBrain:

At BodyMindBrain, we help motivated adults with high-demand lives build strength, energy and resilience by training body, brain and mind as one integrated system.