If you’re constantly managing pressure, deadlines, or trying to juggle family, work demands and your own wellbeing, then it’s easy to normalise stress. But what if driving your body to quietly run in survival mode most of the time? What if your nervous system, not your mind, is behind your irritability, fatigue, or inability to “switch off”?

This is where Polyvagal Theory, developed by neuroscientist Dr. Stephen Porges, becomes a helpful guide to understanding your emotions and behaviours. It offers a powerful lens through which to understand stress, not just as a mental state, but as a physiological one deeply rooted in how at ease your nervous system feels and acts on your behalf.

The Three States of the Nervous System (According to Polyvagal Theory)

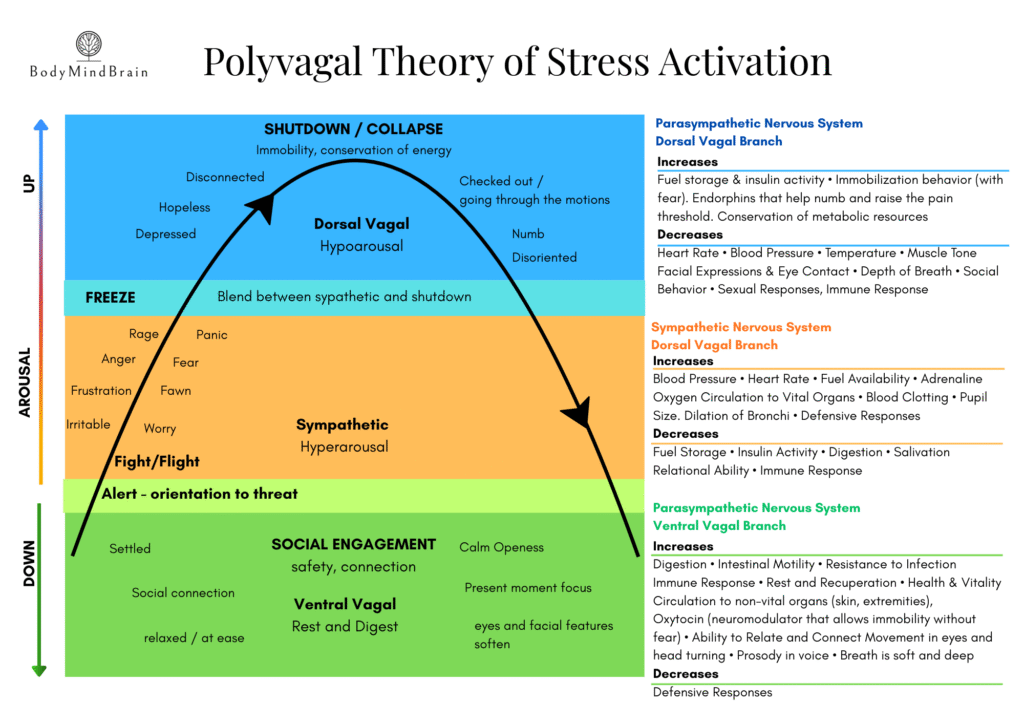

Polyvagal Theory explains that your autonomic nervous system doesn’t operate in a simple on/off way between the over-simplified two branches sympathetic and parasympathetic. Instead, it uses three main branches to constantly assess safety and threat, shaping how you feel, think, and respond. Our nervous system developed over thousands of years, so it wasn’t formed for the world we now live in where demands and stimulation can be with us 24/7. Polyvagal Theory presents 1 sympathetic branch and 2 branches within the parasympathetic nervous system.

If you’d like a refresher on the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system as a while then you can read more here: Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Nervous System

1- Ventral Vagal (Social Engagement & Safety) part of the parasympathetic system

-

- The state of calm alertness, presence, and connection

- Lies at the heart of rest and digest

- Supports communication, open awareness, creative thinking, and emotional regulation

- At work, this is when you’re in flow, engaged, responsive, steady and collaborative with colleagues

2- Sympathetic (Fight-or-Flight Activation)

-

- The mobilisation system that readies the body for action

- Narrows focus, produces urgency, productivity, but also anxiety, reactivity, and restlessness.

- When chronic, can also present as the ‘swan,’ calm on the outside while stressed or anxious on the inside. (a blend of Sympathetic and Dorsal Vagal)

- Common in fast-paced work environments with constant deadlines and pressure

- Energy consuming and fatigue inducing

3- Dorsal Vagal (Shutdown/Freeze & Withdrawal), another, evolutionarily older, branch of parasympathetic

-

- The freeze response occurs when the nervous system becomes overwhelmed and is unable to escape what it perceives as high threat

- Can show up as mental and emotional disconnection, fatigue, brain fog, or feeling emotionally flat or numb

- It is designed to conserve energy, conceal signs of life and ensure survival by, at its most intense, feigning death

- Often mistaken for “calm,” or self-contained, especially in high performers who appear composed but feel detached and are working beyond capacity

- Needs deeper recovery strategies than Sympathetic arousal

Everyones Nervous System is Unique

It’s important to recognise that each person’s nervous system responds differently to stress. What triggers one person’s sympathetic activation or dorsal vagal shutdown may have little effect on someone else. Over time, each of us develops unique nervous system habits, patterns of response shaped by genetics, experiences, lifestyle, and resilience. Similarly, the strategies and time it takes to restore balance after stress and engage the ventral vagal state are highly individual. Therefore recovery approaches and ways to boost resilience also need an individualised approach.

When Calm Isn’t Calm: Chronic Hypoarousal and the Dorsal Vagal Response

Not all stress looks like agitation or anxiety (hyperarousal) . Many high-functioning people operate in a chronic state of hypoarousal, the body’s subtle attempt to survive ongoing pressure by shutting down, conserving energy, and numbing or disconnecting from emotion.

This is the dorsal vagal state, a form of parasympathetic activation that is protective, not restorative.

It can look like:

- Flat emotions, less facial expression, depressed mood or emotional disconnection

- Low motivation or persistent fatigue

- Difficulty feeling joy, inspiration, or connection

- “Showing up and going through the motions” with no felt sense of reward or momentum

- Appearing calm on the outside, while feeling hollow or overwhelmed inside

This state is often misunderstood, especially in driven, responsible professionals who are praised for being “unflappable” or “stoic.” In reality, the nervous system has simply shut down to cope with prolonged overload.

Recognising this pattern is crucial. Without awareness, it can dip into depression or lead to confusion about why you are still able to go through the motions but feel so disconnected. But your system may be doing exactly what it’s designed to do in the face of relentless demand: disconnect in order to survive.

Why This Theory Matters for High-Demand Lifestyles and Workplaces

You might have the job and lifestyle you want, the responsibilities, and the to-do list down to a science. But if your nervous system doesn’t feel at ease enough with the demand, your brain can’t operate at full capacity.

High performers often override these signals with sheer willpower, sport or coping habits that provide only temporary relief, but that’s not sustainable. Your nervous system works automatically without conscious direction. And over time, automatic sympathetic overdrive or dorsal shutdown leads to:

- Reduced emotional intelligence and decision-making quality

- Living in defence rather than co-operation

- Disconnection from colleagues and clients

- Loss or performance, energy and ability to focus

- A loss of meaning or sense of identity

- Difficulty accessing the “top gear” of your performance

Team and Interpersonal Morale Promote Performance

Polyvagal Theory highlights that positive social connection isn’t a luxury; it’s a biological necessity for recovery and protection against chronic stress. We evolved to be safe in community and the workplace is a community. Your brain and nervous system are constantly scanning for cues of safety or danger, what Porges called “neuroception.”

At work, this plays out in subtle but powerful ways:

- Teams thrive when there’s warmth, mutual support, trust, and psychological safety alongside healthy competition and deadlines

- In environments where criticism, micro-stressors, constantly moving goalposts or rushed interactions dominate, people drop into defensive or shut-down states

- Even small shared moments of human connection, eye contact, humour, and presence can help shift someone back toward a more resilient state

How to Use This Insight to Stay Resilient

Understanding Polyvagal Theory helps because it raises awareness and teaches you to:

- Recognise the physiological states you shift through; all of the states described are normal but need to stay flexible

- flexibility within the nervous is trainable with he right recovery methods

- Know that “calm” can be masking shutdown as a result of overwhelm

- If something feels ‘off’ internally, it probably is. Don’t ignore it just because you’re unsure what to do about it

- Being fatigued, wired and disconnected is not something to be pushed through

- Develop daily rituals and tools that shift you back into a parasympathetic state

- positive social connections are biologically designed to help regulate your nervous system

- mastery of nervous system resilience is a blend of individual responsibility for working with our unique nervous systems and social responsibility for the interconnection of our biology

This might include:

- Intentional breathing to re-establish regulation

- Movement to remobilise the body and reduce tension

- Social interactions to download and decompress from your day with people who help you feel at ease

- Recovery strategies to signal the end of the working day (nature, warm bath/ shower)

- Health Technology interventions that improve nervous system resilience, especially recovery from stress, from the inside out

In Summary

You don’t need to feel “stressed” to be out of balance. Polyvagal Theory reveals how the nervous system adapts to chronic stress, often below our conscious awareness, making adaptive decisions on our behalf.

For high-functioning professionals, this theory offers not just insight but a roadmap. A way to understand why things feel off, even when everything looks like a normal day. A guide to reclaim vitality, connection, and clarity by working with, not against, your physiology.

And most importantly: A reminder that true resilience doesn’t mean pushing through. It means creating the conditions, internally and socially, that allow your system to feel safe enough to thrive.

Why Nervous System Training Is Core to the BodyMindBrain Approach

At BodyMindBrain, we use evidence-based methods to support your nervous system at every level, from brain regulation to oxygen metabolism and muscular strength.

Each tool we use targets a different aspect of stress–recovery balance:

-

Neurofeedback helps retrain brain regulation for calmer focus, improved sleep, and emotional steadiness.

-

IHHT (Intermittent Hypoxic–Hyperoxic Training) improves oxygen efficiency and autonomic balance, boosting cellular resilience and nervous system adaptability.

-

Whole-Body EMS improves muscle activation and physical recovery, improving posture and metabolic function.

- Somatic Movement is a movement discipline helping you to release muscle tension and restore easier movement patterns that support efficient and pain free movement for the long term.

-

Stress and Recovery Coaching addresses the behavioural and psychological patterns that keep your system “stuck on” and under-recovered.

The goal is to restore your nervous system’s flexibility, so your body and mind automatically return to balance when life gets demanding.

About BodyMindBrain

We help you break free from the cycle of stress and fatigue and rebuild the capacity to perform at your best. Our integrated system restores balance across mind, brain, and body, helping you recover faster, think clearer, and stay stronger under pressure.

Modern life keeps the sympathetic nervous system switched on, draining focus and slowing recovery. Using advanced, science-backed technologies, we retrain the systems that drive resilience, optimising nervous system regulation, oxygen efficiency, mitochondrial health, and physical strength.

Alongside this, we rebuild the psychological and lifestyle foundations that sustain energy, and protect long term wellbeing.