Polyvagal Theory

Make the most of your nervous system

Understanding Polyvagal Theory

Polyvagal Theory is a way to understand how our nervous system works and how to use that knowledge to help manage stress and find resilience. Understanding your nervous system is the key to finding healthy, emotional balance in life.

What is Polyvagal Theory?

Dr Stephen Porges originator of the Polyvagal Theory has been instrumental in advancing our knowledge of the nervous system and how to use this knowledge to help ourselves feel and function better.

Polyvagal Theory theory, in particular, has expanded our understanding of the Parasympathetic Nervous System because it highlights that it has two branches.

- An older circuit called the Dorsal Vagal Complex (DVC) responsible for more primitive responses, such as the freeze, dissociation and fainting, which has its pathways below the diaphragm and,

- A more recently evolved ventral vagal complex (VVC), also referred to as the ‘social nervous system’, which has its pathways above the diaphragm namely to your heart, lungs, larynx, pharynx, inner ear, as well as the facial muscles around your mouth and eyes.

Polyvagal Theory helps us understand our emotions

Polyvagal Theory has been very helpful to the world of mental health in understanding the nervous system origins of our emotional mood states. One of the two crucial learning points from this theory is that, we now know that the parasympathetic nervous system can shut us down into depressed and freeze states when overwhelmed and that we are not in control of this response. This means that the origins of depression and dissociation are driven by the nervous system in order to protect us from energetic or psychological overwhelm. When we are in a state of confusion, helplessness, panic, shock, rage, chronic pressure, with no apparent options for resolution or capacity to cope with those states, then the nervous system acts to protect us. By numbing, dulling down, disconnecting, freezing, fainting etc., the nervous system has decided that this gives us a greater chance at survival by disconnecting from overwhelm.

Polyvagal Theory and relationships

The second crucial take away is that the ‘rest and digest state’ that helps us wind down is wired together with our social engagement system. Humans evolved to survive and restore through social belonging (safety in the group) and our nervous system reflects this. This means that restorative parasympathetic activity within the nervous system is tied to our being social animals. We evolved to coming together socially and to co-regulate our nervous system with other people, which explains why eating together is such an important part of human culture. We are designed to rest and digest together in the safety of our community. In Western cultures, where competition and individualism is emphasised, it is interesting to reflect on this because the society we have built seems to go against our biological nature. In other words, parasympathetic activity, health, wellbeing, social bonding and co-operation are all inextricably linked at a biological level.

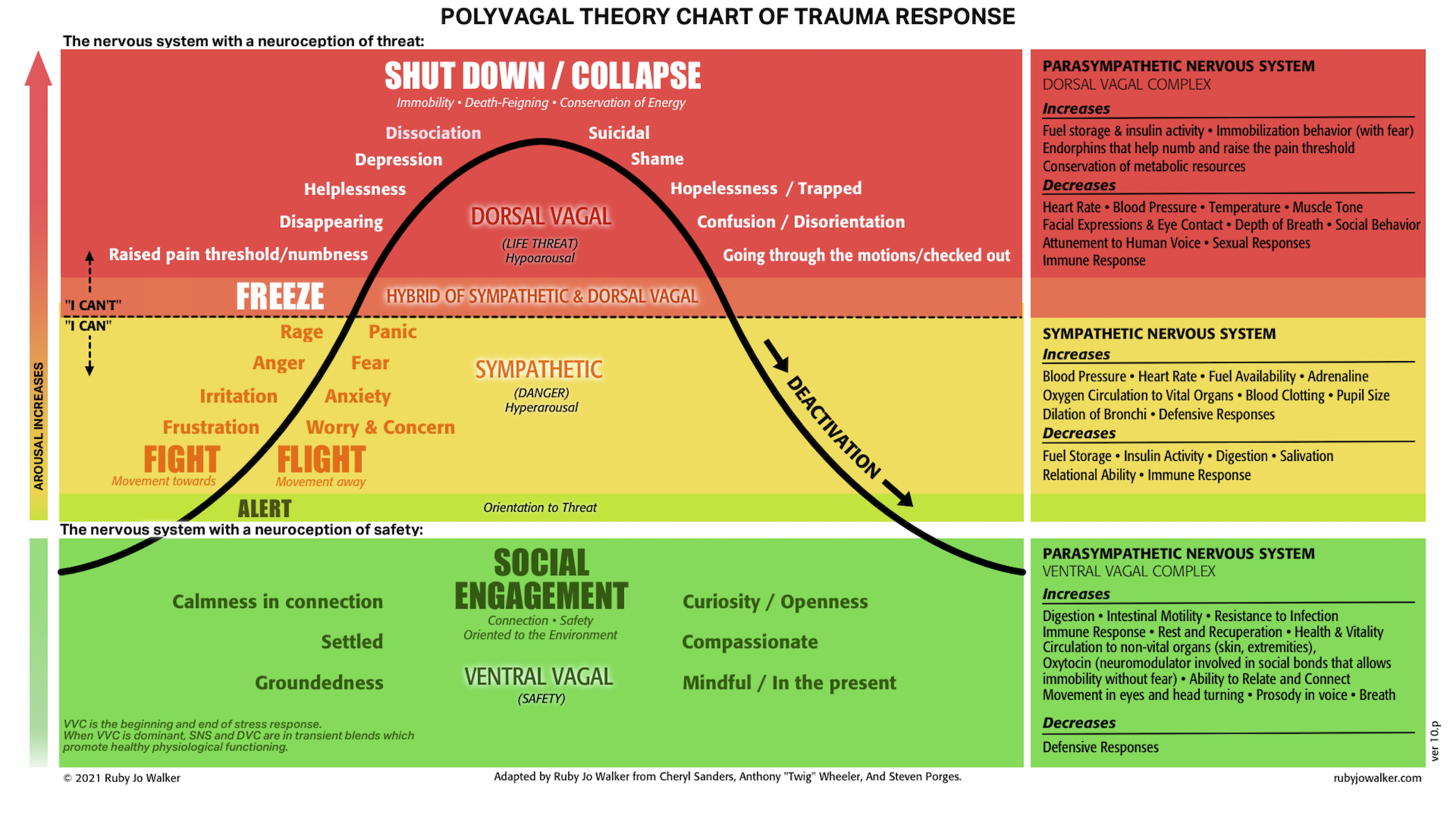

Polyvagal Chart of Nervous System Response Levels

The image below demonstrates how our nervous system responds to different levels of stress and how this is reflected in mood and biology.

Using Polyvagal Theory to help us understand our emotional and behavioural reactions

We now have a way of understanding all the emotional responses that people typically seek help for and how the nervous system drives all these strategies. All reactions that fall outside of the Social Engagement/ safe zone can be considered defensive strategies, driven unconsciously. We need to have defensive strategies but we also need to know how to manage them effectively. It is possible to become stuck in levels of activation that are unhealthy in the long term, so Polyvagal Theory helps us find ways to encourage our nervous system out from danger back to safety. This also means that we can adopt body based strategies for calming the nervous system, which will in turn calm emotions and a person’s outlook. If we do not balance hyper arousal (fight/flight) or hypo arousal (shut down) with Ventral Vagal safety responses, our physical and mental health will suffer.

Its important to note that if you find yourself stuck in hypo arousal or dissociated states, you will need to pass back through the fight/flight stage before transitioning back to safety. If you are using brain and nervous system based approaches, such as NeurOptimal Neurofeedback, to help, then it can also be helpful to find a nervous system based therapist to help you come to terms with fight/flight reactions and any associated any memories driving that.

As a recap, below are the levels of reaction that the nervous system enacts on your behalf when coming under threat:

Level 1 – Attempts at connection: When we feel ‘stress activated’, the first line of defence is often an attempt to use the social engagement system or our social skills to re-establish a sense of connection and ‘safety’ with others e.g. checking in with colleagues, seeking reassurance, seeking physical proximity with others

Level 2 – Fight/Flight/Fix: If we are unable to create safety through connection then we will progressively resort to evolutionarily older biobehavioural defence strategies. First, the sympathetic nervous system responds on our behalf, producing fight or flight reactions to help mobilise us towards self-protection and finding solutions (which is why I use ‘Fix’ as the third F). Here, you might feel shaky, energised, unsettled, anxious, panicky or irritable and angry. Longer term this level produces habits such as avoidance, people pleasing/appeasing, self sacrifice, perfectionism, anxiety disorders, needing to be busy all the time, inability to relax, criticising/ complaining, control seeking or antagonism and angry defensiveness.

Level 3 – Shut Down/ Freeze: – If the sympathetic nervous system is unsuccessful in re-establishing safety and becomes overwhelmed, then it defaults to the evolutionarily oldest part of the vagus nerve, the “dorsal vagal complex” (DVC). This more primitive strategy engages the parasympathetic nervous system into immobilisation or freeze mechanisms such as dissociation, fatigue, numbness and fainting. Here, you might feel tired, dizzy, disconnected or nauseous and longer term this can turn into depression, social disengagement and isolation, emotional flatness and inactivity.

How is Polyvagal Theory helpful for self growth?

Understanding your unique pattern of nervous system activation is helpful when making links with your coping styles. It is also helpful because it highlights how much of the way we are is driven by our body and nervous system. On the Psychotherapy page you will see a picture of a sample ‘coping mode’ illustration – nervous system activation patterns link to your ways of coping. For example, sympathetic activation is often linked to overcompensatory strategies of defence while Dorsal vagal led defences are often linked to avoidant and dissociative strategies. Using a nervous system model alongside psychotherapeutic understanding can help build a full picture of how your body and mind co-ordinate to create habits. It will also help inform more helpful ways to regulate the nervous system and how to engage it in order to you meet your goals in a more balanced way.

If you feel chronically stuck in either fight/flight or dissociation and shut down, or notice yourself bouncing between the two, then it is a good indication that your nervous system has lost its resilience. It is time to help your nervous system to become grounded and efficc=ient as it was designed to be.

Increasing ventral vagal activation

Polyvagal Theory tells us that a good place to start is with the bodily systems and organs that the Vagus Nerve innervates namely the heart, the lungs, the gut, the ears, the pharynx, larynx, the neck and the muscles of the eyes and mouth. There are many options to finding calm and effectively training the nervous system to find balance again. I am also a big fan of using technology to harness our body’s ability to regulate more effectively because it can offer a short cut. I have listed some options at the end.

- Spend time with people you feel comfortable with

- playful activities

- Interactions with a pet like a dog or a cat who can engage a social engagement system

- Gentle neck and eye movements to orient to the here and now

- Gentle movements within tense areas of the body in order to send signals back to the brain about safety and freedom to move

- self massage/ skin smoothing

- Brainspotting

- co-ordinating movement with breathing

- Resonant Breathing to increase Heart Rate Variability

- Roll on a soft pilates ball to gently move the stomach and intestines and encourage the gut-brain communications

- Deep diagphragmatic Breathwork

- ‘The Basic Exercise’ by Stanley Rosenberg

- Humming/ singing or using the voice in a soothing way

- Massage of the inner ear and neck for gentle manipulation of the vagus nerve

- Nature visits

Technology assisted methods for rest and recouperation:

- NeurOptimal Neurofeedback

- Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy

- Red Light Therapy

- Whole body cryotherapy